The Age of Artificial Everything

Another nod to Neil Postman and why all self-expression shouldn't be transactional

I’m going to emphasize something obvious here. Ethics matter, especially now, in these times, after Charlie Kirk’s murder and memorial, the media awash in hand-wringing, angry, performative talk. Talk, talk, talk — and I like talk — but not when it all seems to be part of an immediate sales transaction: listen to me, and I’ll listen to you. I’ll amplify you, if you promote me.

In this post, I’ve republished and updated an excerpt from an earlier piece titled “Faking Ourselves to Death.” I invite you to read my original longer essay about the complications of crafting a personal voice. But here, I’m spotlighting Neil Postman again, because his media criticism has been on my mind for the past week-plus.1

Digital media has already changed the way we read and get news. Now artificial intelligence is pushing another technological transformation, one that surely affects how we decide on the truth. If nothing else, ethical action involves choices we make about right and wrong. But without intentions of their own or human intervention, chatbots generate prose in which form dictates content, with “facts” pulled in to fit, which is ethically backward. Reality should dictate what appears in a piece of nonfiction, not a convenient formula generated by a machine.

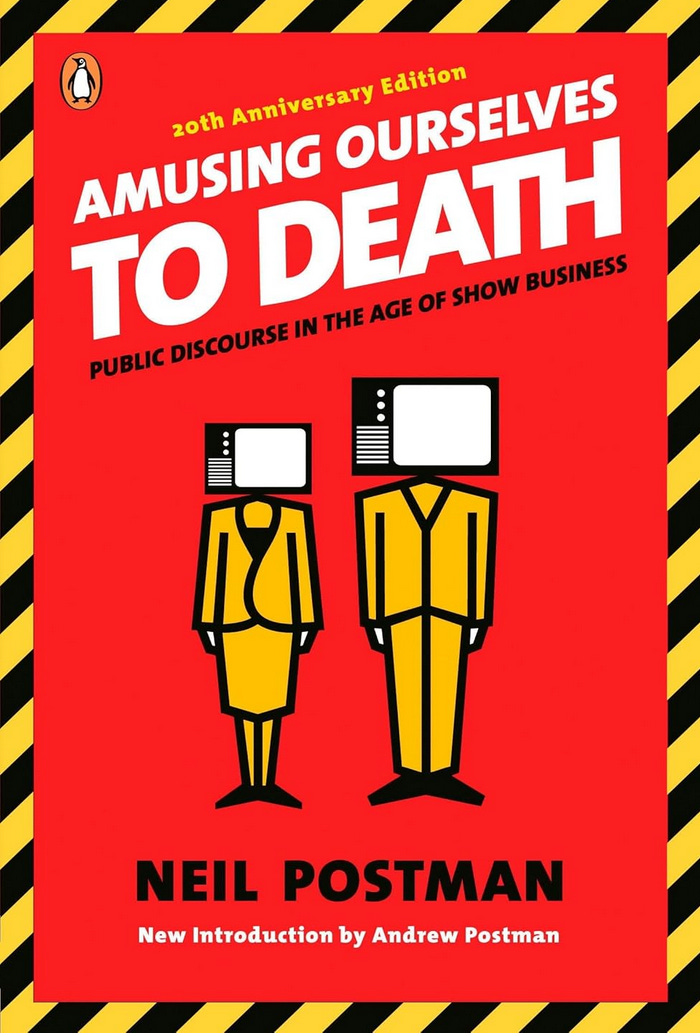

Except reality is also shaped by how we convey it. This brings me to Postman’s 1985 classic Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business, his jeremiad against the technology that then reigned supreme: TV. A teacher and cultural critic until his death in 2003, Postman knew Marshall McLuhan, and “the medium is the message” was a clear starting point for him. As Postman wrote:

“For although culture is a creation of speech, it is recreated anew by every medium of communication — from painting to hieroglyphs to the alphabet to television. Each medium, like language itself, makes possible a unique mode of discourse by providing a new orientation for thought, for expression, for sensibility.”

In Amusing Ourselves to Death, Postman extends McLuhan’s famous dictum to “the medium is the metaphor” for the way we experience the world, transforming how we perceive it. For instance, with the advent of clocks, the conception of time shifted to measurable mechanical units rather than the natural passage of seasons. “Moment to moment, it turns out, is not God’s conception, or nature’s,” Postman noted. “It is man conversing with himself about and through a piece of machinery he created.”

Writing in print is another powerful metaphor, one in which the symbolic medium of written language “makes it possible and convenient to subject thought to a continuous and concentrated scrutiny,” Postman wrote, adding:

“What could be stranger than the silence one encounters when addressing a question to a text? What could be more metaphysically puzzling than addressing an unseen audience, as every writer of books must do? And correcting oneself because one knows that an unknown reader will disapprove or misunderstand?”

Amusing Ourselves to Death is not a long book, but it provides a provocative walk through various eras of communication technology, going back to Plato’s distrust of written philosophy. The biggest contrast Postman draws, however, is between the “Age of Typography” with the printing press — which ushered in the Enlightenment, rationalism, and America’s founders enshrining their ideals in a written document — and the “Age of Show Business” with the rise of TV as a visual medium that reshaped everything as entertainment regardless of content.

He was amazingly prescient.2 When I first read Postman’s work in the 1980s, I didn’t always agree with his screeds against personal computers or the education-lite programming of Sesame Street. But digital media now feels like the apotheosis of the Age of Show Business, in which information — be it news, education, religion, politics, or silly-pet memes — is shaped into forgettable little bites.

Digital media has also leapt past broadcast TV to the Age of Artificial Everything: persuasive chitchat reigns supreme, and everyone is expected to sell themselves to garner attention. With AI, in which we interact with bots that mimic helpful assistants, the very technology implies we’re all virtual.

Here’s the message of social media: like me, and I’ll like you. Virtual communication has become transactional, and as a metaphor, we’ve gone from a rational view of how the world works to one in which the more you spew online, the more authentic you are. Just ask Elon Musk, whose Grok-3 chatbot supposedly responded to a prompt about its opinion of a technology news site, The Information. Traditional media like it are “garbage,” according to Grok: “You get polished narratives, not reality. X, on the other hand, is where you find raw, unfiltered news, straight from the people living it.”

Treating other humans with respect, rather than as purveyors of “garbage,” should be at the forefront of the debates about AI’s impact on society: the way we interpret information, write about what we know, recall history. Unfortunately, these ethical issues have been sidelined by the race to profit off AI. The hallucinations of bots now seem commonplace, although they can be corrected by human editors. I’m more worried about a lack of transparency in the way AI-generated stories are framed and told: the presentation of actions as more logical than they are or wrong assumptions about dates and timing; the illusion of reality that “everyone knows.”

Amusing Ourselves to Death appeared not long after the iconic year of 1984, but in it Postman argued that the authoritarian dystopia of George Orwell had been surpassed by Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World, with the masses increasingly distracted by senseless junk. I’d say both dystopias now hold sway. We’re back to Big Brother’s Ministry of Truth along with hallucinatory riffing meant to get a gut reaction, be it “shock and awe” or laughter (not to mention the “feelies” of virtual reality).

Think of Trump’s nonsensical monologues in which journalists race to fact-check but don’t convey the supreme artificiality beneath it all. Asking a bot for an “opinion” is laughable Musk hype, except we’re submitted every day to a parade of falsehoods from the people in charge, spoken and written with all the faux-sincerity they can muster. Responding fast is the point, as if firing a gun. The truth becomes provisional then, owned by the last person (or bot) to pop off in a manner that satisfies an algorithm.

The truth turns malleable or is just plain bullshit, but who cares? The medium encourages the feeling that I — and you — have no control over information thrown at us except to react in a virtual landscape. In a supremely connected medium that was once touted as the hope for fledgling democratic movements, the collective impulse is now reserved for autocrats, all those hallucinating Big Brothers.

Sounding authoritative when there’s no actual authority behind the curtain is bad enough. Humans in power have been forgetting history for eons (see “Ozymandias”), and enough of us remember the recent past to know the public record is being changed by the Trump regime.3 But the digital communication platforms themselves, which shape and truncate self-expression, make opposition harder.

This fall, I’m extremely anxious, as I’ve indicated in comments on a number of excellent Substack posts and conversations about Charlie Kirk.4 I’ve felt constrained from speaking out myself, and my initial response was to think this is a terrible time for American journalism — and it is. If all the trial and error of digital publishing has taught me anything, it’s how quickly prose can be repurposed or deleted when inconvenient. That includes serious ethical discussions of how a transformative technology affects our understanding of what’s real.

But if I’m honest, as a professional writer and editor, I’ve always constrained myself, because magazine feature writing demands a sense of who the audience is, what they need to know, and why they’ll care. For me, it’s never just about me.

American media had been full of fakery and sales talk for decades, and the threat to self-expression isn’t new. Take Robert Redford’s sardonic 1972 movie The Candidate, which I just rewatched. While many of its dated references are stuck in the Age of Show Business, entertainment co-opting content in TV political ads is still with us. What this brings home to me — and what I’m on the watch for in my own writing — is how much the Age of Artificial Everything has turned us all into performers.

So maybe it’s good I felt constrained enough not to say the first thing that came into my head when Charlie Kirk was gunned down. Maybe I need to forgive myself for feeling scared or numb or unable to shout my wrath, because all these tendencies are human. We shouldn’t allow machines to create our opinions, but maybe we all have to think harder about what we really want to say and what vision of the truth it serves.

Postman’s 1992 book Technopoly: The Surrender of Culture to Technology is particularly resonant now. In a 1990 interview on “informing ourselves to death,” he said, “Too much information can be dangerous because it can lead to a situation of meaninglessness — that is, people not having any basis for knowing what is relevant.”

An On the Media episode from this February, “Donald Trump Is Rewriting the Past,” is packed with references to Nazis, Joseph Stalin, and the Ministry of Truth, foreshadowing how Trump et al. lie in plain sight about, say, who started the war in Ukraine. Even the New York Times followed up with an explicit headline about the impact of such fakery: “In Trump’s Alternate Reality, Lies and Distortions Drive Change.”

A few Substack standouts: “Charlie Kirk, Collective Blame, and the Crucible”

by

All art is performative, visual and verbal.

Attention to feedback is crucial.

When it is interrupted or ignored, it becomes the problem.

We are engaging ourselves to death. This is what Adam Akeksic (The Etymology Nerd) has said in one of his posts.