When I started writing this essay, I thought I might arrive at a brilliant resolution. I also knew that’s not the way reassembling the past works.

In 2023 New Yorker essay by literary critic Parul Sehgal, “The Tyranny of the Tale,” she questions the value of narrative storytelling to transform the self or the world. Toward the end of her piece, I felt another shock of recognition. Of a character in one of Elena Ferrante’s novels who talks about a “swarm” of experience, Sehgal notes:

“A swarm possesses its own discipline but moves untethered. Nothing about the notion of a swarm comforts or consoles. It doesn’t contain, like a story. It allows — contradiction, dissonance, doubt, pure immanence, movement, an open destiny, an open road.”1

The dissonance I feel about “Many Men Watching” is a swarm. It’s me in motion. It’s me connecting Sehgal’s essay to Elena Ferrante’s novels about angry Italian women to Claire Dederer and all the monsters we love to Sgt. Pepper’s fading celebrity head shots and Emily Dickinson writing poems to Death to my brother’s offering of Burning Mom to my mother’s painting to Black Muslims in a French edition titled Gordon Parks. . . .

There’s never a resolution until we die, after which, there still may be no resolution.

The idea of an open destiny is comforting, though. It helps me to frame why I’m so troubled by generative AI. The canned stories ChatGPT and other bots produce can’t move beyond the data of what’s already been. It’s like Andy Warhol’s endless copies, which aren’t original art unless you understand the concept of copying.

The human dimension is beyond the AI, because some things really do vanish. No digital or physical object remains. A machine can’t be shocked by ghosts who reemerge in unexpected places. It can’t leap from the literal to the remembered.

About a third of the way into my brother’s book Burning Mom, on the pages close to where he positioned the image of “Many Men Watching,” he writes:

“So we can’t be apologists for the misuse of technology, nor can we be ignorant about the role it plays (good or bad) in our daily lives. We’ve built our entire value system round it — and it’s maybe a little overrated? In fact, we’re probably doomed if technology continues to be developed by people who base personal identity on what distinguishes individuals from each other as opposed to what connects everyone to nature.

“It’s clear that my mother’s rendering of animals with humans, along with her peculiar penchant for painting crowds of people, was an expression of this truth. We don’t seem to see that the human organism is a radial structure — that we emerge out of our planet in the same way that branches grow from tree trunks.”2

This is another opalescent glitter from his cave, another variation on the swarm and all of experience that can’t be roped into a story with an obvious conclusion.

The human mind and heart keep living forward and radiating outward, arriving at shame and triumph, despair and delight, confusion and comprehension, senselessness and meaning. The dissonance itself is human. The shock of recognizing other voices and stories and times may be the very thing that informs all art.

It’s what makes my mother’s painting so transformative. Yes, “Many Men Watching” is transformative. It’s not easy to live with, but it’s a distillation of her that goes beyond how she hurt or let me down — how I let myself down in not loving enough.

My brother opens his book with two photographs that never fail to make me cry. One is of our mother at 65 — close to my current age — her short hair still dark and nicely styled, wearing a deep-purple turtleneck with her own mother’s cameo brooch pinned above her heart. The other dates to late high school or college, with her hair longer but that same smile, that same cameo on a chain around her neck.

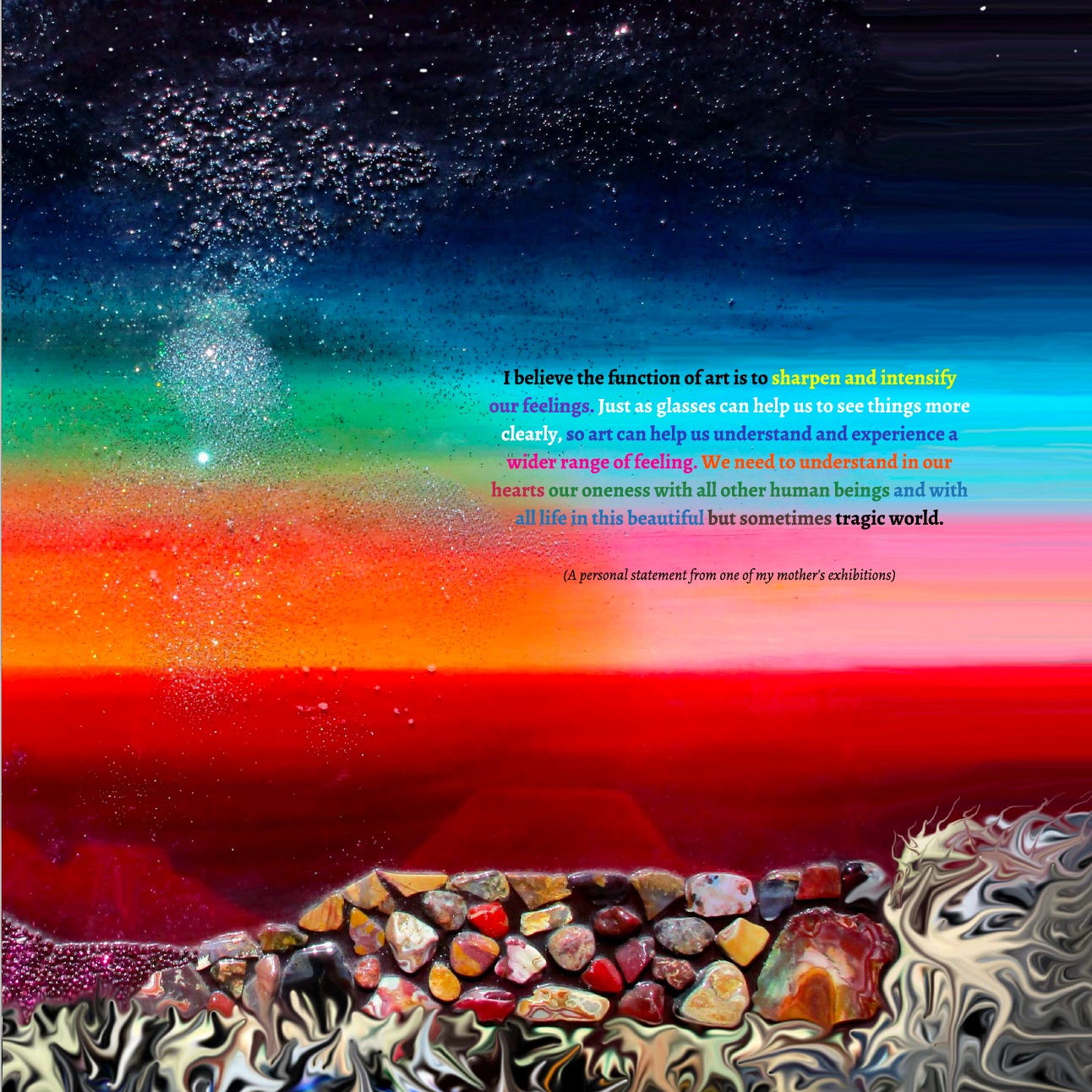

Then he displays words from a personal exhibit statement of hers, superimposing them over part of her 2004 mixed-media work “Sunrise Outback,” the image above.3

This surreal piece by my mother, which she created more than twenty years after painting “Many Men Watching,” shows a rocky landscape with plants whose gnarled roots resemble fingers. I doubt she was thinking about climate change then, but “Sunrise Outback” suggests an altered landscape — we emerge from the planet, in my brother’s words, like tree branches or a swarm of roots.

It’s a people-free world, too, evoking both my mother’s highly personal lens and an uncanny vision of the future. Over the sky, with its rainbow bands of color, her words appear under a strange galaxy of stars:

“I believe the function of art is to sharpen and intensify our feelings. Just as glasses can help us to see things more clearly, so art can help us understand and experience a wider range of feeling. We need to understand in our hearts our oneness with all other human beings and with all life in this beautiful but sometimes tragic world.”4

On another afternoon in 2023, on the Maine island I visit most summers, I walked out on a dark granite shelf beside a rocky beach. I faced the next island and the Atlantic Ocean, the waves frothing only a few feet away, curls of light under a clear sky.

I’d had a silly fight with my husband that morning. I was angry, going over what to say, as I stood on those cratered rocks, stepping closer to the waves and the seaweed-covered ledges, overlooking a shallow tide pool. Farther down the beach, I’d already cried, feeling hurt and alone, before this stony shelf. Grief swam through me like a frantic fish. A squiggle through the shadows, a swarm of sorrow.

Anger comes first, when I lash out at the wrong target, but then it’s an unraveling inner howl, crying for what’s gone, longing for any outcome but this. My grief usually hovers underwater, hiding in shadowed nooks like a tentacled ancient blob, but that afternoon it rose to the surface.

For weeks, I’d been writing about my brother and mother, his burning book, her artwork. I’m a watcher, as vigilantly as the men in my mother’s painting, but they aren’t the only ones watching as I write. My personal crowd of judges is not unlike her seemingly random people tumbling down a Bay Area hillside or a corridor to hell. Amid all the faces, there’s a nun or Frida Kahlo or the Mona Lisa; there’s my dashing father in his thirties, my brother as a boy, my teenage self.

I can stand back and analyze the unspoken debt my mother owed Gordon Parks, of what any of us owe to others, even knowing both artists conjured crowds of watchers through different lenses. Or I can move in close, recognizing her failure and mine for what they are — small, human, gone in a flash — just as I walked closer to the waves breaking on those Maine rocks, treading carefully rather than running to escape.

My good hiking boots were solid. The waves were small but came in fast, a stiff wind in my face. And just as I was about to turn away, I saw purple flecks of light sparking off the water with every curl and release. I thought it was a mirage, but the waves kept rolling, each casting off that purple-blue light, the glitter of opals or sapphires or deep amethyst, a swarm of light.

I took off my sunglasses, hurrying to get out my iPhone to snap a picture so I could record what I was seeing and. . .no more purple. The waves cast only silvery reflections then, a spangle of pale yellow, still a swarm, but more ordinary, disappointing, as if my eyes had failed me. Or the world, because why not blame the world? Until I put my sunglasses back on.

With that, the color returned. I hadn’t lost it. I was seeing the water differently again, the brown lenses filtering out certain wavelengths of light. I’d landed on the right conditions of weather, tide, place, perception — and there they were, flecks of electric feeling superimposed on the glazed yet constantly undulating water.

I wish it were as simple as drawing out my feelings, letting them be whatever they are, not judging myself or anyone else. I wish I could draw that purple light on the water. I didn’t become a visual artist, but there are moments when that’s all I want to do — to draw what I feel and regret and don’t want to lose — to make something others can see just as they see the images my brother created with our mother’s art.

Words on their own are trickier, a second- and third-hand conjuring of the sensory world. Words are nothing and everything I’ve ever known, so I keep reassembling my story to fit this uncomfortable place, one in which I have no control. I can’t say it changes a single molecule or wave of light, but the story is me. It has to be.

There, on the dark rocks, tears sluicing down my face, I saw myself. Through all my swarmy disarray, I saw those I love and remember and want to transform.

These are my glasses, Mom.

In this ten-part essay, I explore one of my favorite paintings by my mother and the way a new understanding of its origins haunts me.

The End. For now.

“The Tyranny of the Tale” by Parul Sehgal, New Yorker, July 3, 2023.

Burning Mom, pp. 81, 83.

For Burning Mom, he broke the original “Sunrise Outback” into two, adding a collage in the first panel and the epigraph text in the second.

Burning Mom, opening pages.

I didn't see that end coming. Love the imagery and metaphors. Beauty seen only through your own lenses. The natural form of a swarm (of birds) came up at a writing conference this past weekend as a possible structure to a poem or story. Here, I felt the swarm embodied in the writing.

"that we emerge out of our planet in the same way that branches grow from tree trunks.”2

Ah, Alan Watts: "An apple tree apples, the earth peoples."

Trees, all plants growing on this blue orb are connected to the natural "web."

Do they not see the sun, feel the wind, taste the soil, smell the air, hear the thunder?