I Transform My Eyebrow

Essay Part 5 • Many Men Watching • confronting my own complicity and rage

A poem I wrote in the late 1980s, “Wanda and the Eyebrow,” allowed me to rename myself. It was published in a literary journal at the time, with young Martha disguised, but anyone reading it would know it was personal.

This poem involved an incident with my mother when I was a teenager. During a fight in our living room, she shoved me up against a wall, waving a pair of manicure scissors in my face. She hated my eyebrows, she screamed — a mess they need to be plucked what is wrong with you LET ME – my heavy mid-1970s brows, ironically evocative of one of her favorite artistic muses, Frida Kahlo. My mother insisted on clipping them if I refused.

I remember her glare, the light sparking from her eyes, the wild scissor blades. I probably refused. I probably screamed back, even though I let her pin me to the wall.

That’s where my memory stops. Or mostly stops, because the numb horror lives on in the way I stiffen at the slightest threat and all the questions I imagine anyone asking.

Why did you let her? Why did you squinch your eyes shut and allow her so close?

In the poem, I condensed what happened years after the fact, but the truth is there. I had become a compositional problem for her. My mother’s raging desire for order spilled out, everything outside her becoming her — an ever-expanding vapor that went beyond her body, saturating the air, infiltrating my lungs — be it my gawkiness or a dirty dish or a spot on the carpet. She had to fix it. She must.

Wanda and the Eyebrow 1

“Those bushy eyebrows never came from my family,”

mother says. “It’s unusual, Wanda. You look unusual.”Wanda is 13. Wanda is a skinny scarecrow

ratty hair like brown husks and woven ritual ropes

from an ancient culture. Not mother’s culture.

A pointed face. Eyes and eyebrows that are too big.

But nothing else is too big. This is my first lesson in relative effects.“I will cut you.”

Mother is holding scissors.

“I will cut you straight and delicate.”

Mother’s face is not frenzied but set.

Mud that has hardened in the California sun.

When she cries, it dissolves

but she won’t cry yet.The scissors. Metal ribbons crossed

and clacking. Clip Clip Clip

Clip. Wanda’s eyebrow

on the ground

curves there in a question

and now Mother cries.

I’m angry at my memories. All the rage I fling at AI and its proliferating misuses, is as tangled and complicated as my relationship with my mother, who was human, flawed, lovable, a powerful influence I could never control, a front seat on chaos. I’ve never felt safe. Stuck with inconvenient knowledge, I transform reality all the time, maybe every time I breathe. The stories take over from reality, and maybe they should.

I made sketches from photographs, too. From elementary school on, I wanted to be a writer, but I also emulated my mother’s obsession with the visual world. I remember drawing the wrinkles and shadows of Ernest Hemingway’s face, copying a famous photograph. It’s a striking black-and-white image, the author in a fisherman’s turtleneck like his character from The Old Man and the Sea.

I now know it’s a 1957 work by Yousuf Karsh, part of major photography exhibitions. But when I drew this as a teenager, I must have seen it in a magazine. I don’t recall thinking that I was copying somebody else’s art. I used black or gray oil pastels, smudging, etching all those fine lines, making Hemingway look older than God.

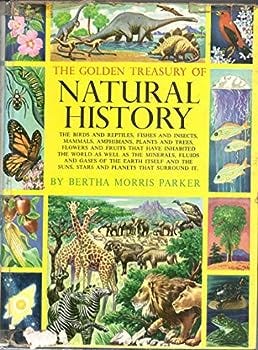

As a child, I also drew birds and giraffes and cheetahs. I remember one drawing of a cheetah in particular on the cover of my fifth-grade report about Africa. I loved animals, and I must have taken the cheetah and all the others from my Golden Treasury of Natural History or well-thumbed issues of National Geographic.

I drew partridges and hummingbirds and kestrels in colored pencil, decoupaging them to wooden plaques. My mother agreed to hang these in the kitchen. I feel tiny wings fluttering inside now, the brush of who I became. I still love birds.

Until that moment in the Paris bookshop, I was blissfully unaware of what inspired my mother’s painting or that we were both copying someone else. It’s one data point from my past, which means there must be countless other voids within, a zillion snake pits I can tumble into without warning. The latest version I’ve created of myself will be shredded by hungry fangs soon enough. It’s already nothing but shreds.

I hate my stupidity. I’m wrecked among the human wreckage, as if I’ve just realized we’re all wrecks built on sloppy foundations.

Maybe feeling wrecked is the point, though. I confront my own failure as a writer every time I consider that my mother may not have been the artist I thought she was — or that the fantasies about this weren’t enough.

I run at my memories, my shameful memories, as if I’m pounding up a steep hill to get through flocks of bullets as fast as I can. Gasping, awash in sweat, muscles cramping, loose rocks pinging away as my sneakers slide — sometimes I trip and fall, ripping the skin of my palms — but I will get this over with. I will come to rest.

I Rip Words from the Universe 2

She almost poked my eye.

Did she know that? No, of course not.

She waved scissors in front of my eyes.But what, Martha?

You were a teenager, a floppy

scraggly kid who didn’t know beauty

if it poked you in both eyes.

We were trimming, just trimming

your name. To make you different.(Trimming — my mother’s word — not cut, slash, poke.

Nothing sharp, just her tongue between her lips,

hard, chapped, serrated lips.)I tried to stand tall and free, to be like the goddesses

in my Edith Hamilton book of myths.

She says trimmed, I say vicious, lascivious, chaos unleashed.

I think my brother was there,

cowering in the hall, our father absent,

so just that trinity after school, the Three of Us

cowering in our different faces.(Maybe groveled or cried,

but crying is like slapping a palm

against a boulder. You hurt yourself.

You break your bones. Yet here I am

breaking more internal bones, speaking to myself as you

when I am addressing the Universe Itself.)I won’t say broken dreams. I refuse.

What did I ever dream about

except that high staircase in the clouds?

I kept climbing, running up a red-carpet runner

squirming beneath my bare feet like a snake.

Running into the clouds.What I remember has faded like a pair

of threadbare jeans, so the memories

are just as ripped and fallen,

ripped from the universe and returning

like so much dusty embroidery thread.

You made me small and hurt,

like my pet turtle jumping beyond the shelter

of a plastic tank, already hating

his fake-green plastic palm tree.You left me to the staircase, Mom,

to climb myself.

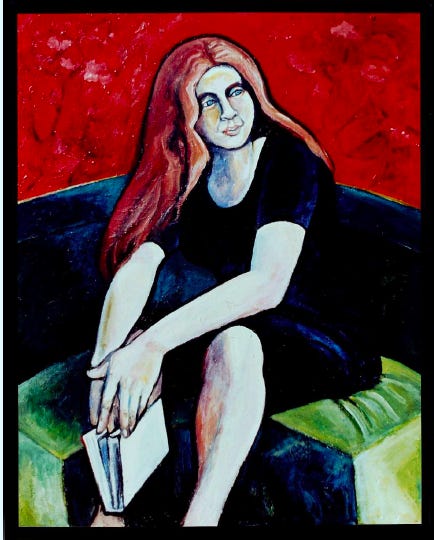

In this ten-part essay, I explore one of my favorite paintings by my mother and the way a new understanding of its origins haunts me.

Next in Part 6: The Human Jumble

“Wanda and Her Eyebrow” by Martha Nichols, Five Fingers Review 6, 1988.

“I Rip Words from the Universe” — my rewrite in 2023.

Visceral and powerful. I have to go back and reread the earliest pieces in this series to see what I think about your concerns about appropriation. I know your mother, though a sometime Gorgon, was very innocent in the world of art and I think at a gut level just saw photos in the paper (here, a magazine?) and they were merely the starting point for her (as you know). When I saw Many Men Watching the men didn't even read as African-American to me. One in the forefront seemed Latino, and as you said several I think are white. If she credited the photos that were the source, would that make her use of them acceptable to you? I think it would to me. But I need to reread those pieces!

Powerful writing. And I am picturing the cultural context around it, too. Intense and wonderful memoir, Martha. Am catching up slowly on the whole.