Her art was a bone of contention between my brother and me even before our parents died. When they were still alive and I was there, he’d always raise the prospect of our mother’s paintings and drawings getting thrown in a dumpster if I didn’t help pay for storage, if I didn’t give more money for their care-home fees, or — the worst cut to my internal canvas — if I didn’t visit California more often than I was already doing.

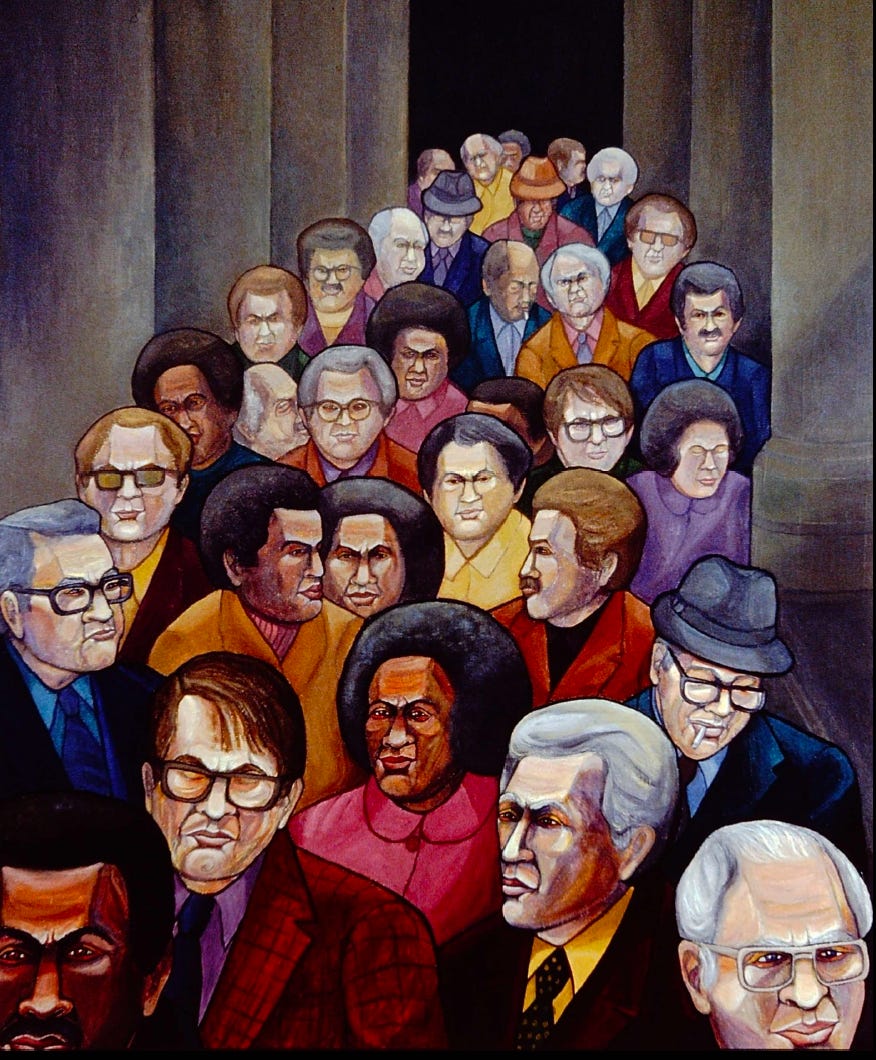

In another email, he told me he thinks “Many Men Watching” got damaged in his Oregon move and was probably “discarded.”1 I see it tossed in that mythic dumpster, crushed under greasy Taco Bell bags and other rotting garbage, the canvas ripped and gouged. In 2023, I began writing about her painting not knowing what happened to it, and I still don’t know, but imagining is worse. It’s like a knife to the gut.

I didn’t expect to feel so much sorrow. Unlike a photograph, which can be reprinted from a negative, a painting is a physical object. It can be destroyed for good. It’s not the same as a human body, but my mother painted very specific, angry, despairing, God-fearing faces. They feel alive in the digital image, but do they still exist, if only in pixels and memory? I think she would have said they were the product of her emotions, her creativity, a life force that can’t be explained.

I think it’s possible they’re gone.

There they are, in my mind, ripped and dying, the rubbery acrylic paint of their faces flaking off. I see dead rats and human feces in the dumpster. I see chicken breasts wrapped in a pink-stained plastic bag, long past their pull and reeking. I see the pink stain on the back of a torn canvas, spreading, until the whole dumpster is heaved into the air by mechanical jaws, all of it spinning in the void, crushed into indistinguishable foamy broth.

It’s gone. You’re gone.

In Claire Dederer’s Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma, her 2023 exploration of the work of artists who did monstrous things in their personal lives, she doesn’t offer easy answers about creative transcendence. I bless her for that. Dederer admits to an enduring love for, among others, Roman Polanski’s Chinatown, a movie or director I’ve never liked. Monsters makes clear just how idiosyncratically and surreptitiously art from the past flows into the lives and feelings of contemporary artists.

Dederer wrestles with not only Polanski but also Woody Allen, Pablo Picasso, Ernest Hemingway, and other male villains it’s now hard for any feminist to forgive. More difficult for me are the morally compromised ones I’m drawn to: David Bowie, Vladimir Nabokov, Raymond Carver. Cancellation of your own fan-girl past is never simple, especially if you’re an art-hungry writer.

In her earlier 2017 memoir, Love and Trouble, Dederer makes it very personal in two open letters to Roman Polanski, in which she connects a sexual assault when she was young with Polanski’s anal rape of thirteen-year-old Samantha Gailey. In “Dear Roman Polanski,” she imagines Samantha’s perspective, overlaying it with her own, questioning Polanski, whom she calls “undeniably a genius,” before answering herself:

“Are you great because you’re sick? What does it even mean to be a genius?. . . A genius is, by nature, bossy. He is the boss of the people who work for him, but also the boss of the people who consume his art. The genius — like the alcoholic — overwhelms you with his vision. He requires you to see things his way.”2

That violation of personhood, so physical with a rape or an assault, but a violation of emotional being, too — this is what Dederer gets right and why it causes such dissonance with the artists we love. Or the people who insist we see things their way.

My mother was not in this same monstrous league, but she did insist that doing art is always worth it, regardless of the pain it causes. She’d be quick to note she meant her own pain, yet I’d counter that there’s plenty of collateral damage when a visionary forces themselves on others. Steve Jobs was a terrible boss, and I don’t let him off the hook just because he was a brilliant designer. He was a monster. So is Elon Musk.

Or I think of Kurt Vonnegut pounding away at his typewriter all day while his young son rambled alone along the highways of Cape Cod. Mark Vonnegut’s 2010 memoir Just Like Someone Without Mental Illness Only More So testifies to the complications and consequences of being “raised by wolves,” in his wry words.3

In Monsters, Claire Dederer poses questions that strike at the core of how much damage we’re willing to tolerate from those who create art. In her concluding chapter, “The Beloveds,” Miles Davis emerges as a particular challenge. She asks:

“What do we do about the terrible people we love? That question comes with another question nestled inside it: how awful can we be, before people stop loving us?”4

My brother accused me of not caring what happened to our mother’s art, which eventually led to the rift between us. Only this year has he asked me to visit him in Oregon, in a little house I’ve never seen. When I do, I’m not sure what I’ll find there. I don’t know which of her paintings and drawings he kept or where they’re stored, even if he’s archived them all digitally. Still, he’s designated me as the executor of his estate. Maybe it’s one more slap, pushing me to decide what to do with her work.

Maybe there’s simply no one else left. I suspect it’s all these things.

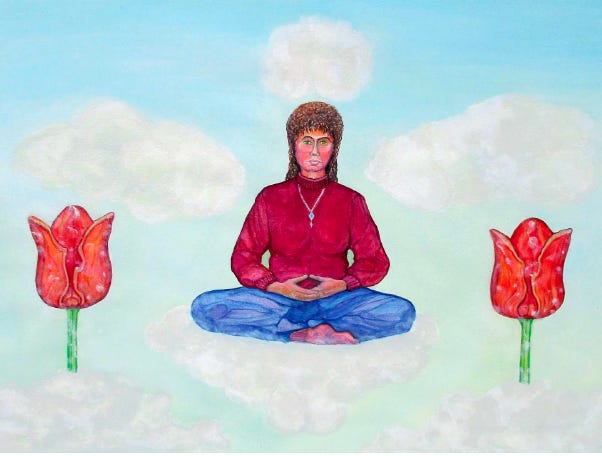

In this ten-part essay, I explore one of my favorite paintings by my mother and the way a new understanding of its origins haunts me.

Next in Part 8: The Glittering Cave

Personal email communication with author, July 5, 2023.

From “Dear Roman Polanski” in Love and Trouble by Claire Dederer (Knopf, 2017), p. 71. Also see “Thoughts on Self-Loathing,” my September 2023 post about Love and Trouble.

“Why Going Crazy Isn’t Just a Good Story” by Martha Nichols (Talking Wriing, Spring 2014).

From “The Beloveds: Miles Davis” in Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma by Claire Dederer (Knopf/Penguin Random House, 2023), p. 255.

Thank you for this, and for the link to your Mark Vonnegut piece also. Just read it — highly recommend it to anyone else who is reading this.