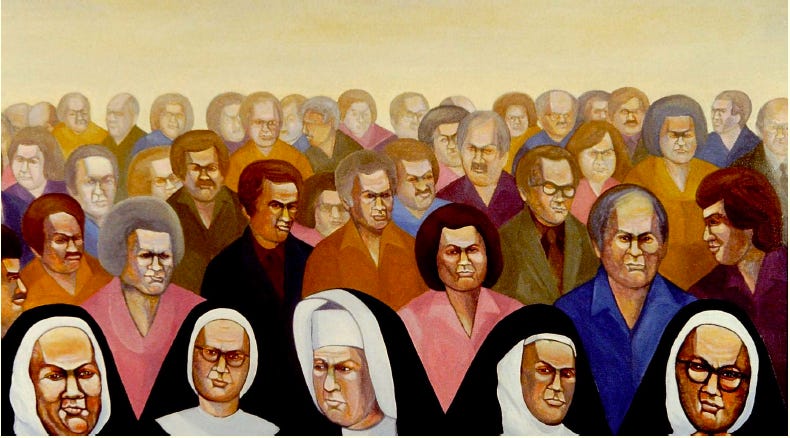

Whenever I remember “Many Men Watching,” I see it hanging in my parents’ garage, before they had moved to care homes and lost their last house by defaulting on the mortgage. Through much of my childhood and in different tract houses, my mother hung her many paintings in the garage, a gallery with car-oil stains on the concrete floor and a sink where my father immersed our bike tires to patch the punctures.

As for our cars over the years — a Ford Falcon that could barely make it up the hill to Cal State where my father taught political science; a Dodge with no air conditioning we rode through the Mojave Desert at night; a tacky brown Plymouth Valiant I learned to drive on — we parked them in the driveway or on the street.

I remember “Many Men Watching” winning a purchase prize in the Alameda County Fair, hanging in a public building somewhere. But when I first emailed my brother about it, he responded:

“I don’t know the exact history of ‘Many Men Watching’ and whether Dad had any input. It may have won some sort of prize, but I would have to investigate that further by digging through her trunk in the garage. However, I will add the Gordon Parks connection to my list of updates.”1

Maybe I’m confusing “Many Men” with another painting. Part of me doesn’t want to know for sure. Yet I’m writing now because sometimes it’s not a choice about knowing. Sometimes the world slams you awake, shakes up the previous mental space filled with hyper-real mountains and valleys, your very own video-game paradise — I have lived my life okay, I am a writer, a thinker, a teacher, a mother, a good person who can’t be blamed for the past — until it’s not okay.

After my mother died in 2013, my brother became the keeper of her extant art, something he intended to archive and document, putting his master’s degree in museum studies to work. In reality, this meant taking all her art from their last garage (after it had been in storage for a couple of years) to a shed I have yet to see on the coast of Oregon, where he then retreated into silence.

He was the one for me to ask about “Many Men Watching.” If nothing else, he is a meticulous keeper of records. But except for occasional emails, in 2023, we had been estranged for years. Our mother’s painting may have changed that, though, in itself a tiny spark of grace. I shared an early version of this memoir series with him, and we’re in closer contact now. My brother’s degenerative illness also shadows how we talk to one another, a few times by phone, possibly in Oregon together this summer.

We remain connected by history and memory, even by love — I can only claim my own feelings there —but my acceptance of what’s happened is shifting, sliding wide of old justifications. I’m asking new questions, recycling the detritus again.

Artistic recycling can seem right and wrong and sometimes both at the same time: ceramic bowls with traditional Hopi designs or ripoffs for tourists? Andy Warhol’s repetition of photos taken by somebody else or infringement of intellectual property?

Determining legitimate “fair use” has always been a matter of degree and intent. Who drew the original image or took the photograph? Whose style or idea is it? Who does the art belong to? Plenty of human artists, past and present, writers and visual artists I revere, haven’t told us about their sources.

Many people, including my brother, think this is okay. I thought I did, too. I know how much any creative work relies on what came before, imitation is the sincerest form of flattery, steal what you love, blah blah blah — even my blahing is recycled cynicism, because I’m inspired by how much we’re in conversation with one another and the past. Critical reviews of art or books necessarily recycle the work itself, using it to transform the writer’s own thinking. Essays in the Montaigne mode may be the ultimate in textual recycling of other people’s work. A few more examples:

David Bowie shamelessly recycled kabuki and R&B and Bruce Springsteen.

Ed Sheeran won a copyright case in which he’d been accused of ripping off a chord pattern in Marvin Gaye’s “Let’s Get It On.”

African American artist Kehinde Wiley recreates classic seventeenth-century military portraits on horseback by Le Brun or Rubens. He puts people of color in the saddle, including his “Napoleon Leading the Army over the Alps.”

The late-eighties painting by my mother above titled “Daughter of God” is a variation on many classical crucifixion scenes. It also nods to Frida Kahlo, one of my mother’s favorite artists, with a self-portrait in a martyred pose depicting her physical and psychic pain. (Our family joked about “Mom on a Cross.”)

Yet none of this explains my shame at seeing the Gordon Parks original for “Many Men Watching.” It’s as if my mother is still in my head, trampling the roses. Here, I’m turning my uneasiness into intellectual dry bones. But big philosophical questions — threats to existence, sense of self, core beliefs — also must be named.

Art is about meaning. It’s about the things we value as humans. Except those values change over time, and now AI systems can recycle the past in milliseconds.

In a New York Times opinion piece, “The Supreme Court Is Wrong About Andy Warhol,” art historian Richard Meyer argues that the court’s 2023 ruling against the pop-art master copying a photograph of Prince does a serious disservice to Warhol.

The art in question is the silk screen “Orange Prince,” which appeared on a 1984 Vanity Fair cover without crediting the original photographer, Lynn Goldsmith. Meyer wrote a brief for the losing side (the Warhol Foundation). The infringement ruling is based on narrow grounds, he notes in the Times. Still, in his view of Warhol, “[t]hroughout his career, the artist was concerned not with copyright but with the right to copy, which he saw both as a creative method and a design for living.”

The right to copy? That doesn’t even nod to artistic transformation or acknowledgment of the original source. I’ve never liked Warhol’s work, but to my mind, it often validates rather than questions the virtual mirage of marketing.

In the 1960s, Meyer points out, the Campbell’s Soup Company said they had no trouble with Warhol using images of their soup cans in his famous paintings — as long as he didn’t put the same logo on his own cans of soup to sell. They didn’t want direct competition, but nodding to the brand? No problem. Warhol gladly agreed.

But the quotes that strike me most in Meyer’s opinion piece seem ready-made for an AI world: “I think everybody should be a machine,” Warhol said in a 1963 interview about whether pop art was really art:

“I think somebody should be able to do all my paintings for me. I haven’t been able to make every image clear and simple and the same as the first one. I think it would be so great if more people took up silk screens so that no one would know whether my picture was mine or somebody else’s.”2

Maybe his pop art was a commentary on the triumph of advertising and celebrity culture, but that hardly feels transformative now. It feels like an excuse.

In this ten-part essay, I explore one of my favorite paintings by my mother and the way a new understanding of its origins haunts me.

Next in Part 4: The Ethics of Copying

Personal email communication with author, June 4, 2023.

See Andy Warhol’s quote in “November 1963: What Is Pop Art? Answers from 8 Painters, Part 1),” ARTnews, 1963.

Martha I’m continuing to really enjoy this series. I had two thoughts one is that acknowledgment of the original source makes a huge difference. The second is wouldn’t be interesting. If novelists were more comfortable listing the books or the authors that had inspired their plots, their themes, their characterizations you can see it with art, but you can’t always tell it with literature

Your mother's paintings are interesting. Both have this feel of a Greek chorus standing in judgment of the viewer. The question you raise about the right to copy is an intersting one. I think about how the artists of the Renaissance learned to paint: by copying the masters. I think the "right to copy" is inherent to the creative process. But having the right to copy is different from the right to proft from the copy or the right to claim the work is entirely original. Is it yours to exercise your right upon? There are lots of stories which are not mine to tell, though I have the right, I guess, to write them.