Why I'm Not an Entrepreneur

How I realized business self-help talk undercuts my writing

Let me take you back to 2014, when I was fully committed to digital media. Up to then, I enjoyed calling myself an entrepreneur. Publishing on my own terms felt liberating. It also seemed realistic. In 2007, when my son went to kindergarten and I headed back into magazine journalism, I discovered that I had to figure out digital media or change professions. So, I started blogging. By 2010, I’d cofounded an online magazine, Talking Writing, where this updated article originally appeared.1

With wonder in my voice, I would tell friends that I never could have imagined being an entrepreneur just a few years before — but I was! I embraced Twitter. I made very little money, but I spent entire days hustling on social media.

By the summer of 2014, when I first began drafting a piece about writers and money, I even found myself blaming authors who complained about losing out in the digital economy. I wrote that concerns about not getting paid “were beside the point, even ridiculous.” I emphasized that I write because I love to write, just as poets and quilt makers are driven to create regardless of financing.

Then came a morning when I suddenly felt my stomach clench. As I studied the draft on my laptop screen, it hit me that I was reading an argument worthy of Donald Trump: The money you make is based on the demand you create, and all the whining about society supporting artists because “art matters” is bullshit.2

Not only was I reading it, I’d written this self-sabotaging screed. I’d taken the anger I had been feeling all year, fueled by my father’s death but also by ominous trends in the publishing industry, and flung it in the wrong direction. The mindset I’d grown so leery of during my time in the 1990s at the Harvard Business Review had wriggled into my brain. It had invaded my own thinking like a creeping little alien, outwardly cuddly, but with sharp teeth.

I still believe in the power of an online magazine like Talking Writing (or a podcast, TW’s current incarnation) to expand the audience for the arts, but I stopped chirping about the joy of being an entrepreneur in 2014. Yes, digital media and platforms like Substack have leveled the playing field, allowing writers to compete in a virtual landscape no longer bounded by nations or an insular gang of New York graybeards. But that means everyone is competing — all the time, against legions of other hopefuls — and the constant competition can be soul deadening.

Let’s see what business thinking looked like in a typical 2014 post. In “Why Every Writer Needs an Author Brand,” Writer’s Relief put it this way:

“You’re promising your audience a particular kind of reading experience, and you shouldn’t let them down. From project to project, maintaining continuity in your voice as a writer is vital to building a successful author brand and establishing a strong fan base.”

By then, such advice had proliferated in writers’ blogs, trade journals, and writing coach sites. (There was even a magazine called Author Entrepreneurship, although it didn’t last.) Phrases like “reader experience,” “fan base,” and “author brand” are rooted in business talk about customer satisfaction.

A decade ago, after spending the past seven years promoting myself online — closing in on twenty years of my work life — I realized that a business focus creates a basic conflict of interest for writers like me. In order to pitch and sell, I needed to shape my content to the audience out there. But as a journalist, I was uncomfortable with being told not to “let down” my audience. That put me on the road to click bait. Maintaining “continuity in your voice” felt even more problematic. Nonfiction writers, in particular, need a trustworthy voice, but that voice may change over time and depending on the topic of a story.

In other words, while the entrepreneurship model works for high-tech startups, grafting it to what creative writers and journalists do is like sticking a brick on an apple tree. Yet I now hear business jargon issuing from literary publishers, indie authors, newsletter writers, and my own mouth: the need for platforms, value propositions, takeaways, economies of scale, branding.

This stuff is in our collective head, and it’s messing with it.

It’s also part of the data used to train the large language models that underpin generative AI. Anyone who’s been reading my posts of late knows I have ethical and aesthetic concerns about the use of chatbots to generate writing, especially writing done in the first-person voice. Entrepreneurial jargon is now eating its own virtual tail, as bots generate hacked-over advice like that Writer’s Relief post.

In a 2025 New Yorker book review, “The Insidious Charms of the Entrepreneurial Work Ethic,” Anna Wiener highlights the latest version of the personal upsell: the LinkedIn post. As Wiener puts it:

“When did people start talking like this? LinkedIn’s style of sanitized professional chatter — to say nothing of the robust cottage industry that exists to support it, from branding strategists and career coaches to software programs designed to generate shareable, safe-for-work content — is of a piece with mantras like ‘do what you love,’ ‘follow your passion,’ ‘bring your whole self to work,’ and ‘make a life, not just a living.’ (The linguistic trend extends beyond the domain of yoga classes and L.E.D. signage in co-working spaces; a recent Times article described Luigi Mangione, the twenty-six-year-old accused of murdering the C.E.O. of UnitedHealthcare, as possessing ‘an entrepreneurial spirit’ in college, because he resold Christmas lights.)”

I love Wiener’s sharp take. It’s also familiar in the way magazine trend features often are. Haven’t we gone down this road before? Oh, yes. Her article is pegged to a 2025 book by Erik Baker, Make Your Own Job: How the Entrepreneurial Work Ethic Exhausted America, one reason I’m revisiting my own 2014 feature. I’d only add that chatbots do a lot of this talking now, which further influences how people talk.3

Recently, an opinion piece by LinkedIn co-founder Reid Hoffman, “A.I. Will Empower Humanity,” appeared in the New York Times. Hoffman, an early OpenAI investor and Microsoft board member, argues that AI can help us make better decisions by retrieving what we’ve left on the digital record, endowing “even the most scatterbrained among us with a capacity for revisiting the past with a level of detail even the novelist Marcel Proust might envy.”

I won’t dig into why this makes me gag on my madeleines. Just consider Hoffman’s vision for sharing data on a corporate platform to “empower” humanity:

“So imagine a world in which an A.I. knows your stress levels tend to drop more after playing World of Warcraft than after a walk in nature. Imagine a world in which an A.I. can analyze your reading patterns and alert you that you’re about to buy a book where there’s only a 10 percent chance you’ll get past Page 6.

“Instead of functioning as a means of top-down compliance and control, A.I. can help us understand ourselves, act on our preferences and realize our aspirations.”4

Realize our aspirations. Now there’s a phrase worthy of all the self-improvement chatterers who have come before, not to mention ChatGPT. Aside from the creepy notion of an AI tracking my “stress levels,” this implies that gamers are in the thrall of shadowy authority figures telling them to take “a walk in nature.” As for “reading patterns,” even if I believe an AI could pin down every book I’ve read, including dusty tomes on my nightstand or ones for which I’ve left not a single word on the digital record, Hoffman’s big idea takes business thinking for granted: it’s all about quantity, metrics, networking, and “our instinctive appetite for rationalism.” It assumes I only care about books I finish, and that the more (or faster) I read them, the better.

No.

It also assumes ideas and feelings are always conscious, that all texts and tweets are the equivalent of dictated reality or worth remembering. While it’s nice to jog my memory on occasion with an AI-prepped photo montage on my phone, data retrieval doesn’t ensure optimal decisions. Taking on old personal data is only helpful if I’m self-aware enough to distinguish between my best self-expression and foolishness. Some of us get wiser as we age.

In fact, my actual realizations often come when I’m in conflict with myself. For instance: this article. When I first wrote it, I’d reached a turning point because my rational decisions didn’t add up emotionally. I recognize and agree with much of what younger Martha said ten years ago, but I’ve added more now.

By the end of 2014, the stories I wanted to tell changed with the deaths of my parents. I wanted to delve into my life with them and write a full-length memoir, an impulse that had nothing to do with author branding. The trouble was, my writing had been influenced by years of crafting 1,000-word blog posts and opinion pieces. It was almost kneejerk, the way I thought in terms of headlines and blurbs, of what I could pitch, of what types of openings drive reader traffic.

That summer, when I tried to jam together memoir scenes from previous blog posts, I felt frustrated. I knew part of what blocked me was the freshness of my grief. But I also suspected that switching so often between marketing and writing gears had affected my ability to tap the unconscious material that fuels my best work.

The thought chilled me — and continues to chill me. At the very least, it took longer to find the necessary creative flow, and my impatience had become a barrier. I couldn’t tell you what material was left untapped, only that I felt pressure to stay on the surface, producing fast and loose regardless of quality.

This was and is my personal struggle, but I’m revealing some of it here to convey why such a conflict is tricky for writers. By 2014, I’d heard too much nostalgic fatalism among older authors about the loss of print, as if the battle was over, so there’s no point in creating a digital alternative. I still don’t believe that. At the same time, I was intimately wound up in the new online technology I used and not altogether comfortable with its impact on my thinking and writing.

Now, this is what comes next in the original version of my article: I won’t say I’ve been co-opted by the companies that own the technology, but I still wonder if I’m being swayed by the entrepreneurial drumbeat of Silicon Valley.

A decade on, I don’t wonder anymore. I know we’re all being swayed and will continue to be swayed unless we reject the premise that we need to sell ourselves for influence. Such a rejection is the equivalent of leaping off a railroad bridge into a canyon of mist. Younger writers might see the leap as professional suicide, and I don’t blame them. I’m close to retirement, so it doesn’t matter to me in the same way, and (oh, right) I’m on Substack. And yet, the struggle to shake off entrepreneurial thinking is even more relevant now, with chatbots spitting out the mediocre prose infesting platforms like LinkedIn and rapidly getting its hooks into news sites.

Way back in July 2014, I laughed when I saw an iPhone, with no apparent irony, displayed in the “Gorgeous” exhibit at San Francisco’s Asian Art Museum — along with Hindu sculpture, a sixteenth-century Persian Qu’ran, and a Mark Rothko painting. Then I thought about why a popular digital consumer product had wormed its way into rooms full of art and sacred texts.

Would the iPhone be considered a “gorgeous” work of art if it hadn’t made such a market splash? I doubt it. I like my iPhone, but I found combining it with that genuinely gorgeous Rothko not only absurd but recklessly obtuse. The previous January, I’d been lucky enough to go to David Hockney’s “A Bigger Exhibition” at the de Young Museum in San Francisco, which included drawings he did on an iPad and smart phone — a fabulous use of new technology by a great artist. But sticking the equivalent of a blank sketchbook on the wall? That was a whole other kettle of pixels.

It’s easy to be seduced into thinking that writers, artists, and entrepreneurs are kindred spirits. Like writers and artists, entrepreneurs must be dreamers, ignited by ideas, willing to put in “sweat equity” and perhaps work for nothing for years because they believe in their products. Maybe that makes them sexy rebels — James Dean “thinking different” on a billboard for Apple. But it doesn’t make them artists. Entrepreneurs look for market openings: what will sell and become popular, what customers want. The goal is payoff on all that sweat, no matter how beautiful the product. If the product doesn’t sell, it’s a failure — not a work of artistic genius that may be understood only years after its creator has died unheralded and penniless.

I sympathize with the ever-present need for creative people to make money. I feel it myself, and I had to be entrepreneurial a decade ago, or Talking Writing wouldn’t still be here. But I’m worried about more than my own digital creation. Despite the rebellious artistic stance — “Here’s to the crazy ones. The misfits. The rebels” — what today’s digital companies really want is this: cheap content to sell apps, devices, ads, and customer data. If that content can be produced by a machine, so much the better.

The executives behind these for-profit corporations used to say “nobody pays for content.” Now they say authors should get subscribers to pay, as if all we need is the right pitch deck to sell “product.” Whatever they say, it’s disingenuous, because they know the payoff is in the technology — not the gorgeous words filling screens.

That’s the bottom line. It needs to trouble us all more.

The original version of my article appeared as “The Trouble with Being an Entrepreneur” in Talking Writing (Fall 2014).

Yes, I invoked Trump before he first became president. Anyone who read the Village Voice or Spy magazine in the 1980s knew him as a self-promoting con man.

At the risk of blowing my own entrepreneurial horn, by the time I left the Harvard Business Review in 1993, I’d written a feature for the magazine called “Does New Age Business Have a Message for Managers?” It covers some of the same ground Wiener and Baker do, with more emphasis on the boho/hippie rebellion that led to business self-help jargon.

Reid Hoffman is far from the worst tech bro, but they all tend to mash up libertarianism and self-help lingo. Hoffman opens his op-ed with an anecdote about users prompting ChatGPT: “Based on everything you know about me, draw a picture of what you think my current life looks like.”

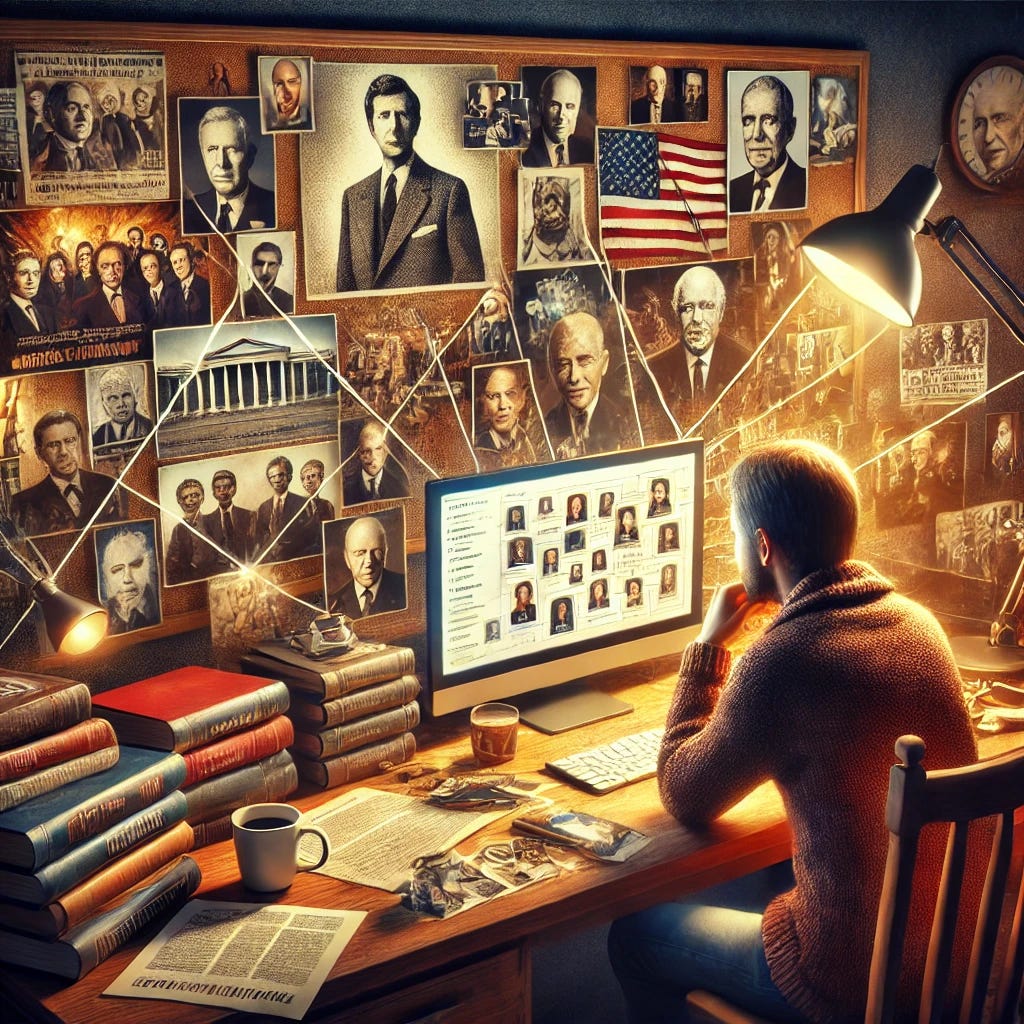

With that prompt, ChatGPT generated the above “portrait” for me. Note that the desk sitter is likely male and all the pictures are men. At least there are stacks of old books and what appears to be a magic crystal connecting the guys with threads of light. However, it’s little different from reading my Lunar New Year horoscope while eating takeout dumplings this week. (Hoffman admits the bot results resemble a “capable carnival mind reader.”)

But in another way, they are similar. Take what this Chinese astrology expert tapped by People said of “those born during the Year of the Dog!” after a challenging 2024:

“‘But the resilient Dog has the intuitive intelligence to adapt and turn challenges into opportunities,’ she explains. ‘This year, the pressure will ease and the Dog will be given a chance to rebuild and upgrade.’”

Yes, 2024 was a bad year. On the other hand, tech jargon like “rebuild and upgrade” has even leaked into the zodiac. It’s everywhere.

I am currently obsessed by light. It is hard to turn this into cash. An obsession with light does not commodify.

— Anne Enright, The Wren, The Wren

I spent 20 years being overtly hostile to marketing and business thinking, intentionally acting against that mindset artistically, and then over the past few years have gone on a long run of reading marketing and business books. And I can say with confidence that I still hate it as much as I did on day one.

The only way that I can think to integrate it into practice is to make the art first without thinking about any of that, and then figure out how to find the people that might be into it. But I'm also working on the assumption that conventional thinking about what can gain an audience are generally more narrow than what's actually possible. I mean, if Merzbow can find an audience by doing blistering noise music, there should be people out there who are into just about anything.

Connecting with those people amongst the competing clamor is always the challenge, and it's important to remember that popularity doesn't translate into money. I'm really trying to figure out ways of doing this that feel authentic, and it's tough to do that sometimes because of how much I hate the hustle aspect. And I should point out that I still haven't figured out how to profit from art.

Also, your original essay is from the same issue to which I submitted a Weird Music excerpt, introducing us for the first time. And I'm now in a similar place to where you were in 2010. I have an unstarted Substack post title "The Slow Turn" sitting in my drafts about this particular transition for me, which has been a progression throughout my adult life. I'll probably return to this comment to mine for nuggets!

I wrote a comment and then accidentally closed the window.. Typical.

Anyways, I agree, Martha. I've always hated the entrepreneur and marketing side of authorship. Back in my naive days, I had the Van Gogh mindset of doing art for the love of art, but I remembered him sleeping in haystacks and starving a lot of the time. It's a delicate balance to survive, play the game, while not selling our souls.

As for the AI quandary, you bring up exactly why it fails in the human arena (among the concerns you've previously brought up). There's no room for nuance.